Both in Seoul and in Washington, the nature of the ROK-US alliance has become a hot topic. Not only the issues of THAAD and the South China Sea, but, more generally, deteriorating relations between the United States and China have made people in both countries concerned about the impact on ROK-US ties. Before this kind of uneasiness became widespread, both countries had celebrated the 60th anniversary of the alliance in 2013 with ample commentary that they were enjoying their best relations ever, and such rhetoric was repeated in 2014-2015. The summits between President Lee Myung-bak and President Barack Obama, and President Park Geun-hye and Obama, kept drawing fanfare in support of this judgment, as the leaders committed their governments to further strengthen the relationship. Thus, tighter ROK-US ties in 2016 have not appeared to be a meaningful realignment, but there is reason to argue that they are a critical part of the ongoing transformation. Yet, in a perverse way, drawing closer actually makes bilateral relations more vulnerable, even to a new anti-American spike. It is the background of recurrent anti-Americanism that can help to shed light on this danger.

The general public of the two countries has shown great support for the alliance. Recent polls show about 90 percent of the Korean public, regardless of age and political affiliation, see the alliance as necessary in the future.1 Attitudes toward the alliance are not much different in the United States. The Chicago Council on Global Affairs in 2012 found that Americans were highly committed to South Korea compared to support for maintaining military bases in other countries. Despite recent general decline in support for sustaining US military budgets and bases overseas, a majority (60%) favor long-term military bases in South Korea.2 This is substantially higher support than for bases in long-time US allies Germany and Japan (both 51%) and Australia (40%).3 With the security threats from North Korea, many Koreans, including even those with anti-American sentiments on various issues, also value the utility of maintaining the ROK-US alliance. According to these poll results, the alliance continues to receive strong support from the public in both countries and from security elites supportive of the Obama “rebalance to Asia” and of Park’s recent rallying of countries against North Korea.

However, recent developments in Northeast Asia have led observers of this region to begin to rethink the nature of the ROK-US alliance. When issues related to the realignment of the alliance are discussed, we can separate the variables that can influence Korea’s decisions on its direction even though those variables are inevitably interconnected. There are exogenous variables that are mostly determined by forces outside Korea. Those variables that can influence Korea’s realignment are mainly US-China relations, Japan’s realignment decision, and North Korea’s future in the region. The endogenous variables can be broadly divided into two categories, even though they are deeply interconnected. These are, on the one hand, the elite’s decisions on realignment, and on the other hand, public support for the evolution of the alliance. This article acknowledges the exogenous variables, recognizing that they impact endogenous ones, while concentrating on the latter in awareness that internal attitudes in South Korea have had a volatile impact.

No matter how solid the ROK-US alliance appears, the positive image above needs closer scrutiny. After all, the mass protests against the import of US beef in early 2008 showed that ROK-US alliance support has fluctuated in the recent past. Some might argue that anti-US sentiment during the protests in 2008 did not necessarily mean weak support for the ROK-US alliance, but it could be conducive to weakening support for the alliance. There is reason to think that the stability of support for the alliance could be put to the test at any time even when relations between the two governments are at a high point. Though policymakers are not bound by and should not just follow public opinion, especially in foreign policy, they will feel political pressure if the public is not content with a certain policy or country. Thus, it is important to understand what kinds of events or policy elements would make the public discontent with certain types of foreign policy. This is especially needed for South Korean attitudes toward the United States in the current period of global and regional instability.

This article analyzes potential threats that could arouse negative sentiment in Korea toward the ROK-US alliance, identifying three main sources that can be seen as causing public support for the alliance to fluctuate. They are interrelated but differ in why and how each makes the alliance vulnerable. First, conventional wisdom holds that ideological anti-US sentiment and certain demographic factors relevant to support for the alliance are related; those ideologically inclined to anti-US sentiment are assumed to be less supportive of the ROK-US alliance. Observers have often argued that at the center of anti-US sentiment are the younger generations, as was proven in 2002. Support for the presence of the US military and the alliance has declined when anti-US sentiment has prevailed. Thus, it is important to see whether anti-US attitudes in the younger generations continue today.

Second, the candlelight vigils for two middle school girls in 2002 and anti-US beef import protests in 2008 showed that those who participate in anti-US protests are not necessarily ideologically left nor guided by ideologically rooted sentiments. Those not ideologically skewed but participating in the protests seemed to react to specific cases under the impact of their emotions and sympathies. When the issues are cognitively difficult to understand, it is difficult to form ones’ attitude without investing time and other resources to understand the issue, making it much more difficult to mobilize people. The electromagnetic pulse issue of THAAD was brought up recently to mobilize people to oppose the deployment. It was mainly because the strategic element and the capability of THAAD were not easy to understand, so those who were only casually following the matter were susceptible to this argument and could be mobilized against it.

The third reason—defining the alliance beyond defense against North Korea—might not become a major factor in the near future, but it has potential in the long term as a source of conflict in bilateral relations. Though this strategic issue has not been a strong concern at a time of continuous provocations by North Korea, we saw a glimpse of the discussion that may lie ahead in Korea when public discourse of THAAD is focused on Korea’s strategic position between the United States and China. If we limit the role of the alliance to the defense of South Korea from North Korea, then public support for maintaining the alliance on the Korean Peninsula after reunification would diminish, if not collapse altogether. Thus, it is important to see how Koreans view the alliance in the future if reunification were achieved. It is heightened aspirations for future middle power salience that may distract from a more sober assessment of Korea’s limitations and a balanced assessment of alliance needs.

Using historical examples and public opinion polls, this article explores anti-US sentiments, including the impact of views on North Korea, and assesses mass responses to ongoing events.

Anti-US Sentiments and the ROK-US Alliance

Under the progressive governments in Korea, it was generally agreed that the ROK-US alliance did not proceed smoothly. Especially during the Roh Moo-hyun government, the alliance was under greater strain than ever before. Scott Snyder noted in 2004 that, “the alliance appears demonstrably less important to both Americans and South Koreans than it was during the Cold War.”4 David Kang once noted that the crisis of 2002 showed how far the two countries had drifted apart in their foreign policies and perceptions.5 Former ambassador Donald Gregg, who is considered more positive to Korean progressives than any other US ambassador who has served in Korea, said the year 2004 was “the lowest point in the history of the alliance.”6

To grasp what contributed to decreased public support for the alliance, we need to see what happened in that time period and its potential to recur, analyzing what was in the public mind and what kind of political context existed when anti-Americanism peaked. Though anti-US sentiment in Korea has a long history, I focus on recent history and its foreign policy context.

During the Roh Moo-hyun administration, on the surface, there seemed to be no problem in the alliance. Roh publicly hailed the alliance, made an official visit to the United States, visited US bases, and, importantly, agreed to send troops to Iraq at US request despite some domestic political damage. Nevertheless, the main reason behind a strained alliance was diverging perceptions at the elite level in regard to what constituted the principal threat to each country. With the prevailing anti-US sentiment triggered by the deaths of two middle school girls and the rhetoric of the presidential election in 2002, the public generally shared the political elite’s perceptions of the security environment Korea was facing. In January 2004, a poll showed that 39 percent considered the United States the greatest threat to ROK security, while 32 percent regarded North Korea as the biggest threat.7 Such perceptions—at odds with US denial that it constituted a threat and its belief that it and South Korea were in full agreement on the nature of the North Korean threat—led to difficulties in policy coordination regarding North Korea. During the Roh period, from the US perspective after the North had broken away from the framework operating since 1994, it was important to synchronize policies to pressure the North to dismantle its nuclear program. In contrast, South Korea was inclined to urge the United States to engage the North by offering it tangible inducements to resume the freeze in its nuclear activities. The US government considered North Korea a rogue state and called it part of the “axis of evil,” whereas the South Korean government and the public at that time viewed it as kin, i.e., ultimately part of one nation on the Korean Peninsula. Anti-US sentiments in Korea—linked to disputes over support agreements, including troop deployments, command relationships, and the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA)—were well publicized in the United States, which, in turn, led to the erosion of support for the alliance among its policy elites. This rapid degrading in support for the alliance was never expected. Though a certain level of anti-US sentiment had long existed in Korea, expressed by the political oppositions and students, none foresaw these developments threatening to downgrade the alliance until this occurred with great rapidity when Roh was president.

Why did the South Korean political elite have different views of North Korea? The gap in economic capability between the two Koreas had widened sharply since the late 1970s. South Korea’s economy had grown dramatically even while experiencing international economic crises. South Korea could finance a growing defense budget even though its share of the GDP actually declined. With the loss of any sense of parity between South and North, South Korea’s fear of the North diminished drastically. Also, President Kim Dae-jung’s policy toward the North and the 2000 North-South summit reinforced the public’s belief that a war between the two Koreas would be very unlikely. During the Kim Dae-Jung and Roh Moo-hyun governments, the South Korean government was much less concerned with the North’s intentions and capabilities as sources of threats. Political elites during those time periods were anxious to avoid backing North Korea into a corner. Younger elites and politically mobilized youth (the “386” generation) believed that crisis on the Korean Peninsula would result from conflicts between North Korea and an imperialistic United States, to the point where they believed that the United States posed a bigger threat to the Korean Peninsula than North Korea.

Related to this different perception of the security threat coming from North Korea, there was a huge difference in how to deal with nuclear proliferation issues on the peninsula. While nonproliferation tops US policy priorities toward the Korean Peninsula, the ideologically left-leaning Korean political elite and the public seemed to consider the quest for nuclear weapons by North Korea to be legitimate, arguing that the reason why it pursued nuclear weapons was to increase bargaining leverage in negotiating with the United States. We can assume a couple of reasons behind this thinking: First, believing that South Korea could be easily devastated by a conventional artillery attack, people conveniently concluded that North Korea did not have to pursue nuclear weapons if its aim was to attack South Korea; second, in even more naive reasoning, people found it unimaginable that North Korea would ever use nuclear weapon against its ethnic kin. These sentiments linger and could be invoked anew.

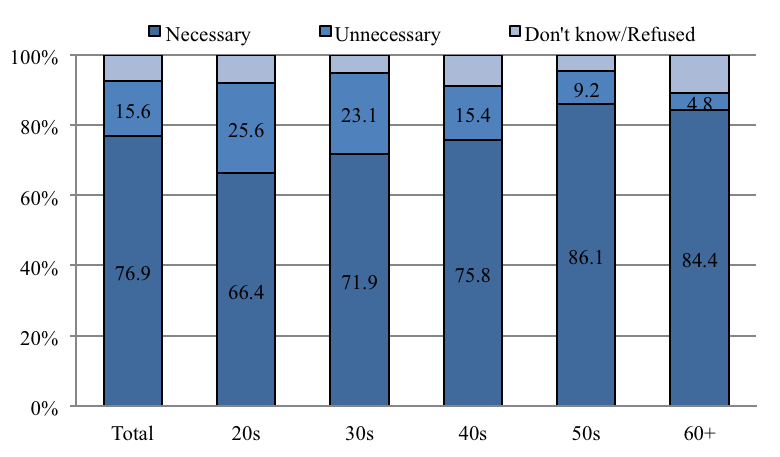

Until recently, Korean observers posited a dichotomy between the generations above and below the age of 40 in political orientation, which was an important indicator of anti-US sentiment. As they gained prominence in mainstream politics, the younger generations, who had experienced the democratization process and were ideologically to the left, were at the center of anti-US sentiment. Survey results confirmed the conventional belief that they are more prone to being on the ideological left and to harboring anti-US sentiments. However, they revealed a difference between those in their 20s and those in their 30s and 40s. When asked with which statement they agree more, 76.9 percent of Koreans said that USFK is necessary for Korea’s security, and 15.6 percent answered that it is not necessary and causes many social problems. As expected, the younger generations tended to make the second choice, while the older ones made the first choice. The figures were 66.4 percent of those in their 20s, 71.9 percent of those in their 30s, and 75.8 percent of those in their 40s choosing the first.

Figure 1. Necessity of USFK8

|

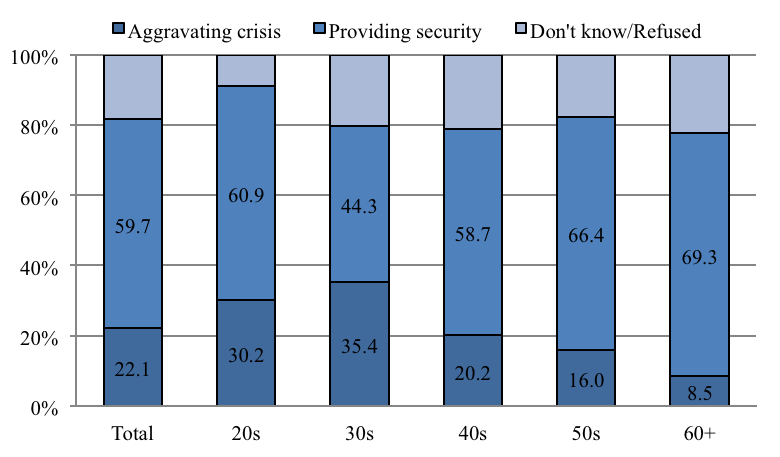

Given two statements—that the United States is providing security to Korea, and that the United States is aggravating the crisis on the Korean Peninsula—59.7 percent agreed with the former while 22.1 percent concurred with the latter. 44.3 percent of those in their 30s chose the first option as did 60.3 percent of those in their 20s. This was not very different from the 58.7 percent of persons in their 40s, 66.4 percent of those in their 50s, and 69.3 percent of those in their 60s and older.

Figure 2. Perceived Security Role of USFK9

|

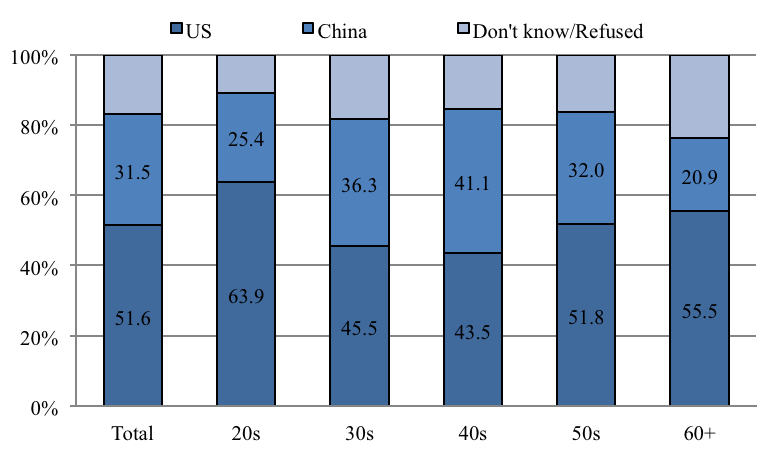

Between two statements—that Korea should strengthen the alliance with the United States, and that Korea should strengthen its relationship with China—51.6 percent of respondents said the United States, while 31.5 percent said China. While 51.8 percent of those in their 50s and 55.5 percent of those in their 60s agreed to strengthen the US alliance, as many as 63.9 percent of those in their 20s also chose the United States compared to only 45.5 percent in their 30s and 43.5 percent in their 40s. People in their 30s and 40s show consistent attitudes toward questions related to the United States distinct from older Koreans, but those in their 20s are different. When the issue at hand is almost purely security related, they respond more like their counterparts in their 50s, and 60s and over.

Figure 3. Preferred Alliance Partner: United States vs. China10

|

If the issue involves an emotional reaction toward the United States, those in their 20s are reacting more strongly than other generations, as seen in responses to the terms “USFK,” and “social problems.”

Mass Reactions and Mood-changing Events

It was not only progressive governments that saw fluctuations in the alliance, as seen in the anti-US beef import protests in 2008 just after Lee Myung-bak took office. His period was considered by many the high point of the ROK-US alliance after 10 years of progressive governments in Korea. Restoring the alliance to its proper place was one of the priorities of his government; however, the alliance was put to the test. Although the anti-US beef protests started from objections to a specific policy, they turned into widespread, general anti-US protests. Some argued that the mass protests in 2008 were mainly coming from the opposition’s dissatisfaction with the election results in 2007; the ideologically progressive left who supported the opposition in the presidential election also mobilized those-anti-US beef protests. However, it turned out that those who participated in the series of protests in 2008 were more numerous than those core opposition groups.

The other mass anti-US protest was the series of candlelight vigil protests after the acquittal of the US soldiers who had accidentally run over the middle school students during their military drill in 2002. Those protests shocked many observers not only because of their size but also due to the composition of protesters at that time. Many observers had believed that anti-US protests were planned and conducted by students on the ideological left and mobilized progressives. However, in these two events demographic details and evidence of the political attributes of participants pointed to ordinary people who had not actively been involved in any kind of political protests. These examples could be echoed in future scenarios.

Kim Sunghan in 2003 categorized the demonstrators as populist groups by comparing them with both ideological groups and pragmatic groups;11 groups emotionally mobilized in response to particular incidents versus typical ideological groups composed of left wing intellectuals, students, and progressive politicians. Pragmatic groups, in turn, refer mainly to NGOs with specific purposes on such issues as SOFA, crimes committed by American soldiers, burden-sharing, environmental issues, and the operational command system.

According to Kim Jinwung in 1989, anti-US sentiment in Korea can be broadly categorized into two types:12 ideological and emotional, mainly driven by repulsion to particular policies and actions. In this view from 1989, the majority of Koreans shared emotional anti-Americanism, while a very small number of people have ideological anti-Americanism. One can assume that those two events in 2002 and 2008 triggered innate anti-US sentiment among the general public, who had no intention of taking an ideological position toward the United States. Since the beginning of the 20th century, Koreans have suffered from contention among the major powers on the peninsula. With the US involvement and the establishment of the ROK-US alliance, there has been this notion of a sacrifice of Korean sovereignty for US security. Previously, it was only ideologically rooted progressives who expressed their anti-US inclinations. However, with the rapid growth of the economy and nationalist sentiments, those without ideological inclination also felt that Korean’s basic sovereignty to protect its people was breached, as some Koreans were benefitting by keeping the ROK-US alliance.

The vast size of anti-US protests had a significant influence on domestic politics. Sentiment triggered by the candlelight vigil protests eventually led to Roh winning. The three-month mass protests in 2008 led Lee Myung-bak to reshuffle his advisors and cabinet members just months after the start of his administration. In those examples, masses mobilized emotionally in anti-US public demonstrations had an impact on Korean politics.

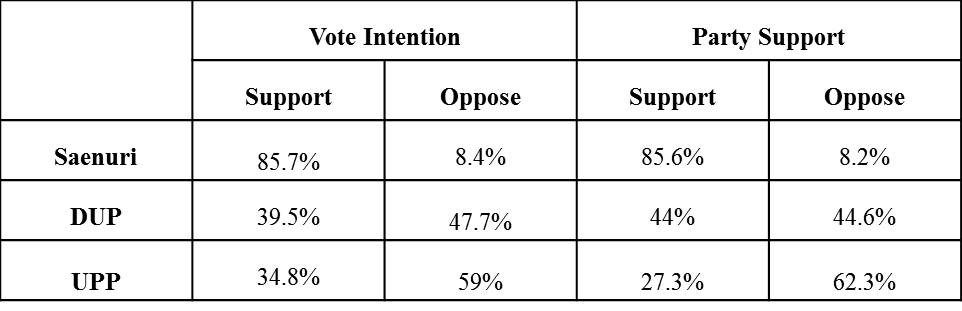

We find some differences in the case of the 2012 general election. The Democratic United Party (DUP) and the United Progressive Party (UPP) made a strategic electoral alliance to support only one candidate against the ruling Saenuri party candidate in each electoral district, drawing on lessons from previous elections when the opposition had split the anti-ruling party votes. They remembered the political consequences of triggering mass public mobilization on the basis of anti-US sentiments. To realize a united front against the ruling party candidates in electoral districts, the DUP had to make concessions to the much smaller UPP, even reversing its previous decisions on the KORUS FTA and Jeju naval base, which had both been pushed during the Roh Moo-hyun government. That kind of reversal might have appealed to core constituents with an anti-US ideology and served to consolidate the party leaders’ positions within their own party. However, it failed as an election strategy. Polls taken during the 2012 general election showed that those issues did not arouse the public. First, 60.5 percent said the “KORUS FTA should proceed without any setback,” while 29.1 percent responded the “KORUS FTA should be rescinded.” 85.7 percent of those inclined to vote for the Saenuri Party agreed with the KORUS FTA, 8.4 percent were for rescinding it, while 39.5 percent of those who intended to vote for the DUP agreed to proceed in comparison to 47.7 percent for rescinding it. Voters supporting the UPP, unyielding in their opposition to the KORUS FTA, were 34.8 percent in support, whereas 59 percent favored rescinding it. The most active backers of rescinding were students (44.9%) and those in their 20s and 30s (43% and 45.1%, respectively).

Table 1. Attitudes on KORUS FTA by Vote Intention & Party Support13

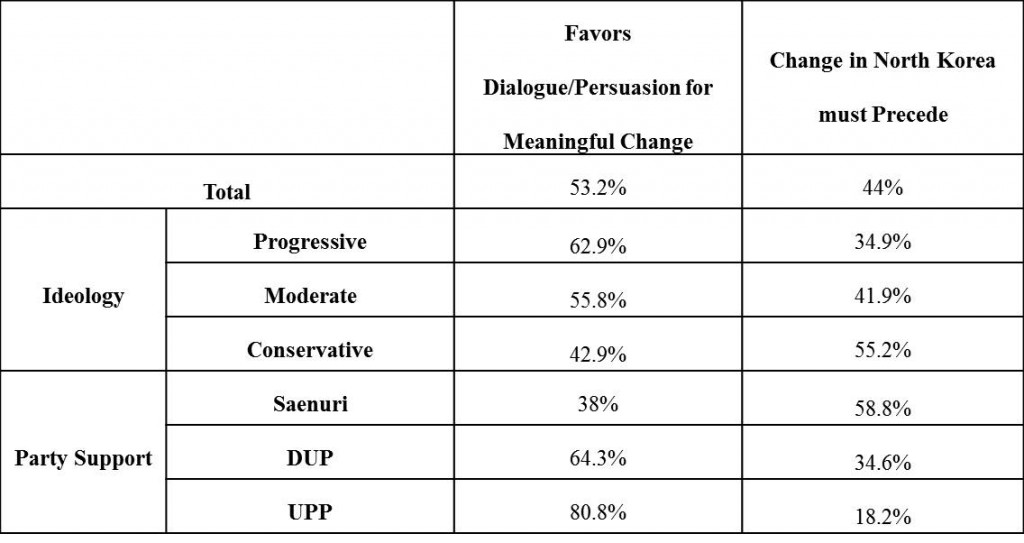

Second, even though North Korea policy did not become the central issue of the last general election, it has been significant in many elections. Towards the end of the election campaign, North Korea launched a rocket, and some expected that the news could unite the conservative groups. We examined opinions on North Korea policy based on two policy objectives: “South Korea should grant economic aid, hold dialogues, and persuade North Korea to elicit meaningful changes there,” and “South Korea should not resume economic aid to North Korea before it shows signs of potential change.” 53.2 percent agreed with the first objective, whereas 44 percent supported the second without a significant generational divide. 55.1 percent of the respondents in their 20s agreed that economic aid should not be granted without preceding changes in North Korea—higher even than for respondents in their 60s and older (51.7%).

62.9 percent of the progressives favored dialogue and persuasion, while 34.9 percent stated that change in North Korea must precede granting any aid. For conservatives 42.9 percent preferred the former, whereas 55.2 percent supported the latter. There was no sharp divide in opinion between the two groups, which used to be the case for the government’s North Korea policy. As for supporters of the parties, 38 percent of Saenuri Party backers stood by the policy of dialogue and persuasion and 58.8 percent were unyielding about “no change, no aid.” In fact, 34.6 percent and 18.2 percent of the supporters of DUP and the UPP respectively supported “no change, no aid”; the radical divide in opinion on North Korea policy only was found in the distinctiveness of the UPP.

Table 2. Views on North Korean Policy by Ideology & Party Support14

Admitting that there were many other factors that could affect the voters’ decision-making, the impact of an anti-US policy package was considerably weaker compared to those cases in 2002 and 2008. The public was not mobilized by intentional campaigns by the opposition at that time, although the opposition put much effort into triggering anti-US sentiment among the public as a reason to vote against the ruling party. The capability of attracting more voters from the middle was already diminished in 2012 because the KORUS FTA and the Jeju naval base were problematic for the opposition since it had to reverse decisions made while in power.

In 2002 and 2008, the public reacted emotionally. First, those cases were framed in terms of Korea’s sovereignty being infringed by the United States, imposing its own rule on Korea for its own benefit. The public thought that the soldiers who killed (even if inadvertently) the two middle school girls should be tried in Korean court and punished accordingly. Also, they believed that responsible higher US government officials should apologize. At first, USFK denied responsibility for the accident. The Ministry of Justice of Korea indicted two American soldiers in the local court and asked USFK to give up jurisdiction, but it stuck to its rights by citing SOFA. As a result, those soldiers were acquitted in a military tribunal on the US military base and left Korea five days after their acquittal. People consequently believed that sovereignty had been seriously infringed.

In early 2008, South Korea and the United States reached an agreement on the sanitary rules that Korea would require of US beef imports, which allowed imports of all cuts of beef (both boneless and bone-in) and certain beef products, including those from cattle over 30 months old. Processors had to remove material known to risk BSE prion transmission (also known as mad cow disease). The ban on the US beef imports had been imposed in 2003 after mad cow disease was detected in US cattle. Lee visited President George W. Bush at Camp David on April 20, 2008, and agreed to lift the ban, but he was accused of doing so in haste, giving the United States unwarranted concessions to receive a favorable reception, particularly with respect to ratifying the proposed FTA. The sovereignty infringement argument held that Korean people’s health was being sacrificed for US economic benefit.

Anyone who heard the news of the 2002 deaths or was nervous about food safety could be susceptible to an emotional appear. The public could see its government as failing to do its duty to protect its citizens, and that the United States was acting at the expense of Korean people’s lives.

In contrast in 2012, the issues that the opposition pushed forward were the KORUS FTA and the Jeju naval base, which led the public to calculate whether these policies would benefit them or not and were perceived as ideological conflicts between the conservatives and the progressives. Also, when an environmental issue arose on a US base in Korea, USFK apologized first and promised to take care of it properly, and when the military police of USFK handcuffed a Korean citizen and took him to a US base, both the Korean and US governments were alert to the sensitivity of the issue.

It is not surprising that the opposition has recently brought up the issue of the electromagnetic pulse of the X-band radar system which accompanies THAAD. Before Park announced that the ROK and United States would deploy THAAD, the opposition’s main arguments were strategic concerns with regard to Korea’s relations with China and capability concerns that THAAD was not effective in defending the Korean people from North Korea’s missile attacks. However, the element that triggered a strong protest in Sungjoo, the site for the deployment, was the negative effect caused by electromagnetic pulses from the radar system. People feared for their health and crops. This argument worked similarly to the US beef import issue in bringing people onto the streets.

The ROK-US Alliance and its Future Role

The ROK-US alliance was formed after the Korean War. Even though it is a mutual defense treaty, it is an asymmetric alliance. There have existed tensions between keeping the alliance for security and pursuing more autonomy. As North Korea is right across the border and has posited almost permanent security threats, the Korean people have acknowledged the necessity of maintaining the alliance, but they do so ambivalently. In September 2012, when asked whether they think that ROK-US alliance is necessary “in the future,” about 94 percent of respondents said “Yes.” Even among those who identified themselves as progressive, 88 percent agreed. This support drops about 10 points when asked whether the alliance is necessary “after the reunification”—4.4 percent among conservatives (from 97.8% to 93.4%), and almost 16 percent among progressives (from 88% to 72.3%).15

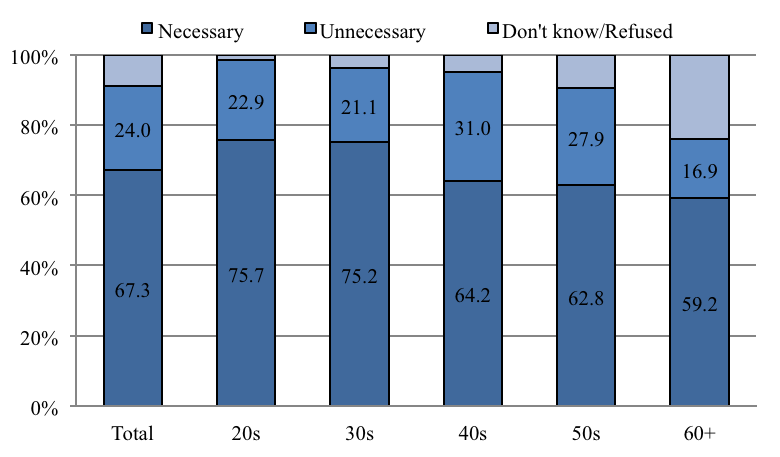

About a year later in a survey in September 2013, we can see some differences. The support for the alliance in the future drops a little—89.6 percent positive, but only 67.3 percent saying that the ROK-US alliance will be necessary after reunification. Older generations see less value in maintaining the alliance after reunification, as opposed to 75 percent of those in their 20s and 30s, 64.2 percent in their 40s, 62.8 percent in their 50s, and only 59.2 percent in their 60s.16

Figure 4. Necessity of ROK-US Alliance after Unification

|

For Koreans, the utility of the ROK-US alliance will diminish after Korean reunification. It was conventional wisdom in the United States that support for continuation of the alliance will diminish if the North Korea threat is gone. However, a 2010 Chicago Council survey found that Americans do not limit the utility of the alliance within the defense of South Korea from North Korea. 80 percent of Americans said that even after the two Koreas reunify, the United States should maintain its alliance with Korea. Among those 80 percent of Americans, about 43 percent agreed to maintain US ground troops in Korea to serve as a counterbalance to China. Only 14 percent of Americans said that United States should end the alliance following reunification.17

Koreans started to feel the pressure of choosing between the United States and China much more heavily as China expressed its strong opposition to THAAD deployment in Korea. As the THAAD system is scheduled to be deployed in the first half of next year, it may be the main question facing prospective presidential candidates. North Korea’s series of nuclear and missile tests have forced the opposition not to say much on this issue, but it is inevitable that it will be at the core of the debates when it comes to Korea’s strategic position. This could be fertile ground for the revival of anti-Americanism, especially if pressure on Seoul, Pyongyang, or Beijing exposes gaps in strategic thinking.

Conclusion

The realignment in 2016 appears to boost the ROK-US alliance significantly and reduces any prospects for a new spike in anti-Americanism. The KORUS FTA has defied the warnings of Korean critics. The intensified sense of threat from North Korea has lessened this factor as a reason for questioning the purpose of the alliance. To the extent that South Koreans have had a zero-sum view of relations with China and the United States, the growing disenchantment with China makes the United States look better. Yet, both the recurrent history of revivals of anti-American protests and sentiments, including at times when few had traced their causes or expected them to have such an impact, as well as the difficult situation facing South Korea at this time, should alert observers to the potential for anti-Americanism surging again before long. In this sense, the realignment must be seen as incomplete and even fragile, and subject to reversal by electoral results and to sharp contestation in the midst of aroused public dissatisfaction.

Anti-Americanism could spike again from a sense of hopelessness, resentment against US pressure coming from an assertive reading of Pivot 2.0, anger at perceived abandonment by a US administration quick to shift its priorities, or from emboldened policy by a new president in Seoul who believes in middle power empowerment despite intensified regional polarization. There are many pitfalls lying in wait, which leaders in Seoul and Washington will have to prepare to forestall or counteract. The potential for a divide over the United States will likely grow in 2017, and in these circumstances, awareness of conditions that arouse anti-US emotions will be required to steer bilateral relations forward and keep the 2016 realignment on track.

1. Asan Institute for Policy Studies, Asan Daily Poll (2013). Unpublished raw data (Data collected: Sep 5-7, 2013).

2. Ibid.

3. Chicago Council on Global Affairs, “Working Paper on the US-ROK Alliance,”October 15, 2012, https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/sites/default/files/2012_CCS_US-ROKConferenceReport.pdf.

4. Scott Snyder, “The Beginning of the End of the US-ROK Alliance?” PacNet 36, August 26, 2004.

5. David Kang, “The Avoidable Crisis in North Korea,” Orbis 47, no. 3 (June 2003): 495-510.

6. “Kim Jong-Il: The truth behind the caricature” Newsweek. February 2, 2013, http://www.newsweek.com/kim-jong-il-truth-behind-caricature-140251.

7. Y. Hong, “US ranked as the most threatening country to South Korean,” (in Korean) Chosun Ilbo,January 11, 2004, http://www.chosun.com/editorials/news/200401/200401110271.html.

8. Asan Institute for Policy Studies, Asan Daily Poll (2013). Unpublished raw data (Data collected: Sep 5-7, 2013).

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. S. Kim, “Anti-American sentiment and the ROK-US Alliance,” Korea Journal of Defense Analysis 15, no. 2 (2003): 105-130.

12. Kim Jinwung. “Recent Anti-Americanism in South Korea,” Asian Survey 29, no. 8 (1989): 749-763.

13. Woo & Kang, “Electoral issues and vote choice,” in Vote Choice of Korean Electorates: 2012 National Assembly Election (Seoul: Asan Institute for Policy Studies, 2012).

14. Ibid.

15. Asan Institute for Policy Studies, Asan Annual Survey (2012). Unpublished raw data (Data collected: Sep 1-24, 2012).

16. Asan Institute for Policy Studies, Asan Daily Poll (2013). Unpublished raw data (Data collected: Sep 5-7, 2013).

17. Chicago Council on Global Affairs, “Constrained internationalism adapting to new realities,” September 16, 2010, https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/sites/default/files/Global%20Views%202010.pdf.

EMAIL

EMAIL  LIST

LIST

SHARE