Discussions of security challenges to Myanmar’s past governments have tended to focus on land-based threats, primarily insurgencies associated with ethnic armed organizations.1 This does not mean, though, that Myanmar is unconcerned about questions of maritime security. This is underscored for instance by the expansion of Myanmar’s Navy (Tatmadaw Yay) since the State Law and Order Restoration Council came to power in 1988.2 Indeed, maritime security issues and challenges have come to increasingly preoccupy Myanmar’s recent governments: both military and nominally civilian. At stake is not so much the South China Sea, although Myanmar shares the interest of other member states of ASEAN in freedom of navigation, but its own maritime boundaries and jurisdiction in the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. What instruments has Myanmar relied on to address maritime security issues and challenges? What are the interests that Myanmar has been seeking to protect? In what ways is Myanmar already involved in more than just unilateral measures in the area of maritime security? This brief analysis is divided into two parts: first, it examines Naypyidaw’s position on the South China Sea conflict. In this regard, particular attention is paid to its management of the issue when it held the ASEAN chairmanship in 2014. The focus then turns to management of its various maritime interests closer to home, including the delineation of maritime boundaries, baseline claims, and non-traditional challenges.

Myanmar and the South China Sea

Myanmar has land boundaries with Bangladesh, India, China, Laos, and Thailand. Only to the south does it open up to the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. Accordingly, unlike several fellow members of ASEAN, Myanmar is not a claimant in the South China Sea conflict. But Myanmar does have an interest in secure sea lines of communication connecting East Asia and the Indian Ocean, including those that pass through the South China Sea and the Strait of Malacca. This is particularly true now that Western trade and investment sanctions against the country have mostly been lifted and trade flows with regional countries in Southeast Asia, Japan, and the United States are rising.

As a member of ASEAN since 1997, Myanmar has on a routine basis quietly subscribed to and supported the consensus positions on the South China Sea forged by the association. This also applies to the diplomatic efforts that resulted in the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, signed by ASEAN and China. Even when Myanmar could be seen to have opted for limited alignment with China in order to deal with Washington’s regime change challenge during the years of the George W. Bush administration, Myanmar did not visibly undermine ASEAN’s joint principled position on the South China Sea. At the same time, Myanmar has not taken a position on the sovereignty and maritime claims put forward. This should not come as a surprise as Myanmar has traditionally been committed to neutrality in its foreign policy. Under U Thein Sein, Myanmar has re-embraced also in practice the declaratory principle of non-alignment and remained committed to an independent and active foreign policy.

How then did Myanmar react to the row that prevented ASEAN from failing to issue a joint communique at the 2012 ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting (AMM) when Cambodia was the ASEAN chairman? At the time, the Hun Sen government was opposed to incorporating into the communique the draft text relating to the South China Sea—put forward by Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam—that made reference to the 2012 Scarborough Shoal confrontation between China and the Philippines as well as to waters Vietnam considers part of its exclusive economic zone (EEZ), but for which the Chinese National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) had issued exploration block tenders. Phnom Penh also rejected all relevant draft amendments, leading observers to conclude that China was exercising its influence with the Hun Sen regime. Interestingly, Myanmar apparently did not speak out against even the initial 2012 draft text containing the references deemed most sensitive.3 Such a position could primarily have been the consequence of the country’s commitment to stay neutral and not to become involved; alternatively, the Thein Sein government could have concluded that it should stay quiet despite or because of its own more critical attitudes toward China. Further research will tell. What is clear, however, is that when Myanmar assumed the ASEAN chairmanship in 2014, silence on the South China Sea conflict was certainly not an option. After all, the chair is responsible for the statements the association releases on the occasion of the two annual summit meetings as well as the yearly AMM and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) Ministerial Meeting.

Myanmar as ASEAN Chair

Pointing to Naypyidaw’s “special” (Pauk-Phaw) relationship with China and its status in ASEAN, Myanmar observers predicted that Naypyidaw would approach the South China Sea dispute “in an unbiased manner.”4 Indeed, notwithstanding the fact that bilateral ties with Beijing had deteriorated over several issues in the initial years of the U Thein Sein presidency, in taking over the chairmanship Myanmar assumed the role as a neutral. The government even seemed optimistic about claimants being able to make further progress on the Code of Conduct (CoC) during its chairmanship. This apparent optimism built in part on the limited progress achieved under the chairmanship of Brunei in so far as China and the ASEAN countries had finally agreed to start discussions on the CoC. However, trust building among the key claimants was considered crucial for further progress in the ASEAN-China talks.

During Myanmar’s chairmanship, it was soon tested as a crisis manager. In early May 2014, an oilrig owned by the CNOOC was moved into contested waters near the Paracel Islands. This prompted a storm of nationalist outrage not only in Vietnam, where violent protests targeted Chinese economic interests, but also across the wider region about China’s “new assertiveness.” Under Myanmar’s stewardship, ASEAN basically reaffirmed the line that the grouping finds unacceptable any proprietary behavior by China. Expressing “serious concerns” about developments in the chairman’s statement at the twenty-fourth summit in May 2014, ASEAN reiterated its basic position that freedom of navigation and over flight needed to be maintained and called, among other things, for all parties to the DOC to undertake full and effective implementation, and to exercise self-restraint. In addition, ASEAN foreign ministers released a statement in which they expressed not only their “serious concerns over the ongoing developments in the South China Sea,” but also expressly argued that these “have increased tensions in the area.”5 This separate statement avoided finger-pointing but, arguably, accommodated slightly sharper language than usual—in China’s direction. The rig was subsequently withdrawn early. Despite having reportedly been pressed by President Xi Jinping on the South China Sea issue,6 Myanmar continued to maintain good balance in further releases, accommodating all sides to some extent. The joint communique released at the AMM 2014 for instance did not support but “noted” Manila’s “Triple Action Plan” (TAP) that had called for an immediate moratorium on specific activities such as land reclamations.7 The chairman’s statement at ARF only stressed the need for a peaceful resolution of the dispute in accordance with universally recognized international law,8 and, observers suggested, did not quite reflect participants’ heated discussion.9 The chairman’s statement released by Naypyidaw on the occasion of the twenty-fifth ASEAN Summit simply restated the members’ concern over the situation in the South China Sea, without further elaboration. In short, Myanmar did much better than Cambodia in responding to the grievances of ASEAN claimants and maintaining ASEAN unity while not overplaying their hand vis-à-vis Beijing. Consequently, assessments of Myanmar’s role as chairman have been positive, both within the country and outside.

Myanmar’s Maritime Security Concerns

If Myanmar has maintained a neutral and balanced position when addressing disputes in which Naypyidaw is not directly involved, how has the country dealt with its own maritime security challenges? These have related to a combination of maritime boundary disputes, contested baselines and operational assertion, as well as non-traditional challenges, such as illegal fishing. These challenges are all linked to Myanmar’s geography, not least its extensive coastline.

Measured from the mouth of the Naaf River on the border with Bangladesh to Kawthaung, the border crossing from Thailand, the Myanmar coastline has a total length of 2,228 kilometers. The Rakhine coastline measures 713 kilometers, the Ayeyarwaddy Delta coastline 437 kilometers, and the Tanintharyi coastline 1,078 kilometers. Myanmar’s waters also comprise 852 islands of various sizes.10 These are distributed in the Bay of Bengal, mostly off the Rakhine coast, south of the Ayeyarwaddy Delta, and form the Myeik archipelago off the Tanintharyi coast. In addition, Myanmar also has sovereignty over the Coco islands that geographically form part of the Andaman and Nicobar islands archipelago. In the 1990s, Great Coco Island was rumored, especially by Indian analysts, to host a Chinese-run signal intelligence gathering station that was monitoring Indian naval activity in the Andaman Sea/Indian Ocean. Despite repeated denials, these rumors were dispelled only in 2005 by India’s then chief of naval staff.11 (Notably, India itself established already in 2001 a tri-service command in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands).

Maritime Disputes

Myanmar has maritime boundaries with India, Bangladesh, and Thailand. The maritime boundary with India was settled already in the 1980s as was, for the most part, the maritime boundary between Thailand and Myanmar. In the latter case, a dispute has, however, continued regarding the ownership of three small islets (Ginga Island/Ko Lam, Ko Khan Island and Ko Ki Nu), which has on occasion sparked the occasional naval confrontation. That said, the broader significance of this issue seems limited. The key issue for Myanmar until the late 2000s, therefore, was the delimitation of the maritime boundary between Myanmar and Bangladesh, which, in the words of Dr. Aung Myoe, had “the potential to escalate into a major armed conflict.”12 The two countries had negotiated at a political and technical level between 1974 and 1986 and while having provisionally agreed on a territorial sea boundary in 1974, they had failed to delimit their respective EEZ boundary. A key question was whether in setting their maritime boundary the principle of equidistance should be favored, as argued by Myanmar, over the principle of equality, as favored by Bangladesh. No negotiations on the maritime boundary had taken place between 1986 and March 2008. But in 2008, Dhaka formulated a new maritime claim that from Myanmar’s perspective was “far more aggressive.”13 Against this backdrop, a naval standoff occurred in November 2008 after Myanmar engaged in exploration activities in a disputed area supposedly rich in gas deposits.14 With bilateral diplomacy proving fruitless to find a mutually acceptable resolution, Bangladesh took the case to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) in October 2009 to secure the delimitation of the maritime boundaries with Myanmar in relation to the territorial sea, exclusive economic zone, and continental shelf. Myanmar accepted the jurisdiction of ITLOS.

Initial deliberations concerning the delimitation of the maritime boundary began in early September 2011, and 15 public sittings were organized the same month. Bangladesh insisted that the maritime boundary in relation to the territorial sea should be the agreed line in 1974, which, it argued, had been reaffirmed in 2008. However, Myanmar denied that the territorial sea boundary had been settled conclusively. The tribunal decided to reject Bangladesh’s line of argumentation. It accepted instead Myanmar’s claim that the “1974 Agreement” was not legally binding because it was conditional on an agreement to delimit all contested waters. The tribunal also ruled that there was no tacit or de facto agreement as regards the delimitation of the territorial sea. It also did not uphold the estoppel claim put forward by Bangladesh as there was no indication that Myanmar had caused Bangladesh to change its position to its detriment. At the same time, the tribunal agreed with Bangladesh’s claim that St. Martin’s Island, which lies in the northeastern part of the Bay of Bengal about 8 kilometers west of the northwest coast of Myanmar, should have a 12 nautical mile territorial sea in the area where the territorial sea of Bangladesh no longer overlaps with Myanmar’s territorial sea. Bangladesh committed to respecting access for Myanmar around St Martin’s to the Naaf River.

With respect to the EEZ and the continental shelf, the tribunal decided that there be a single delimitation line for both. Again differences existed on the method: whereas Bangladesh strongly argued that the equidistance line was inequitable and therefore favored the “angle-bisector method,” Myanmar rejected the latter.

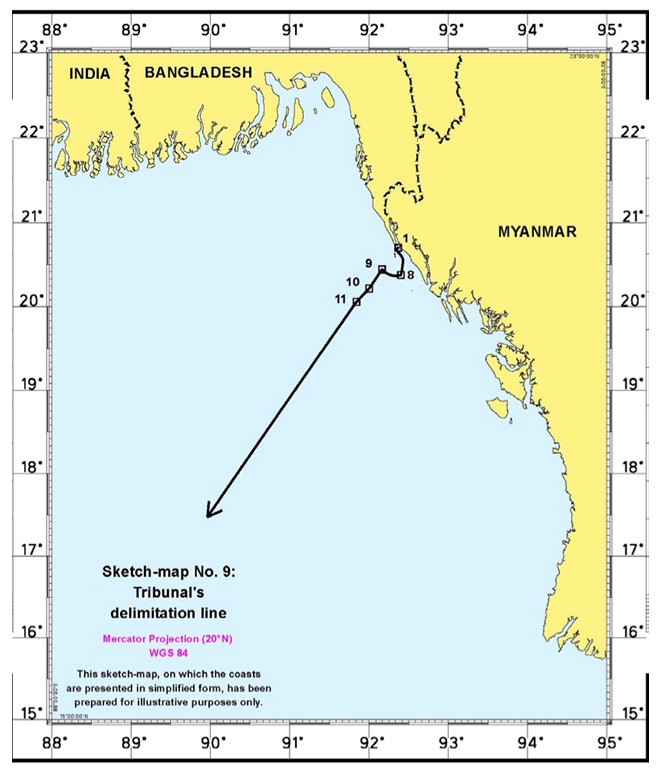

Map 2.

The tribunal decided to apply the equidistance/relevant circumstances method that in effect made for an adjusted equidistant line. St. Martin’s Island was not given any effect in drawing the delimitation line of the EEZ and continental shelf.15 This was also applied for the delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles, where coastal states have sovereign rights to resources on the seabed and its subsoil. Both Bangladesh and Myanmar had for different reasons maintained that the other state had no entitlement to the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles. In coming up with its decision, the tribunal felt that the delimitation of maritime boundaries was without prejudice as regards to the exercise of delineating the outer limits of the continental shelf. Both Myanmar and Bangladesh accepted the tribunal’s decision.16 The ruling marked a victory for diplomacy and international adjudication. After its submission in December 2008, Naypyidaw submitted an amendment in July 2015.

Contested Maritime Claims and Operational Assertions

A very different kind of security concern for Myanmar has been a consequence of what the United States takes to be excessive maritime claims. At issue is a challenge by the United States to Myanmar’s straight baselines, particularly as concerns the Gulf of Martaban, but also other maritime claims, such as restrictions Myanmar has imposed in relation to its claimed EEZ. In practice, this challenge involves US policy to operationally assert freedom of navigation against countries that are perceived to put forward excessive maritime claims, which encompasses the regular violation of these excessive maritime claims by US naval assets.17

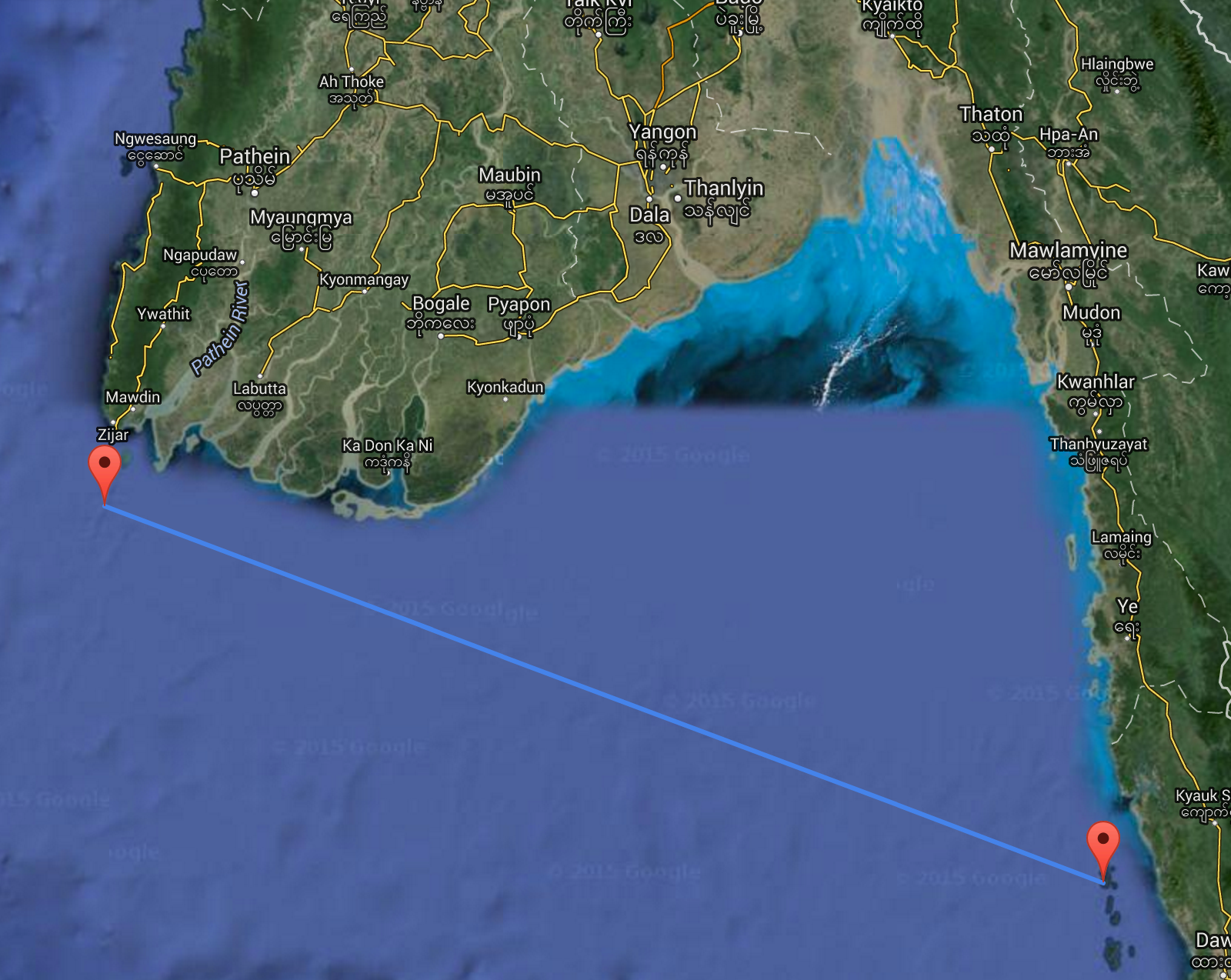

In Myanmar’s case, it was in November 1968 that the chairman of the Revolutionary Council of the Union of Burma, General Ne Win, declared the boundary of the country’s territorial sea. In this context, the military government issued its baseline claim “by reason of the geographical conditions prevailing on the Union of Burma coasts, and for the purpose of safeguarding the vital economic interest of the inhabitants of the coastal regions.”18 Specifically, it drew 21 straight baseline segments, from the southern point of Mayu Island on the Rakhine Coast to the western point of Murray island on Thanintharyi coast. Significantly, this included a massive single baseline segment across the Gulf of Martaban, which has a length of more than 220 nautical miles between Alguada Reef (Pathein Light) and Western Point of Long Island (see Figure 4), making for one of the longest straight baseline claims in the world. The effect was that the distance thus created between land and the baseline was as much as approximately 130 nautical miles.

Map 3. Straight Baseline Gulf of Martaban

Though justified by Myanmar with reference to the vital economic interests of the inhabitants of the coastal region,19 Washington has considered the claim to be excessive and, hence, openly challenged it. While recognizing that straight baselines are permissible where the coastline is deeply indented or cut into (see Art. 7 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)), it has argued that Myanmar’s straight baselines “depart to an appreciable extent from the general direction of the coast of Burma and [that], therefore, the system does not comport with international law.”20 Moreover, Washington also justified its protest as follows: “Burma…by drawing a 222-mile straight baseline across the Gulf of Martaban has claimed about 14,300 square kilometers (an area similar in size to Denmark) as internal waters which, absent the closing line, would be territorial sea or high seas.”21 Myanmar is, for sure, not the only country in relation to which Washington argues there is a case of excessive maritime claims, not even in Southeast Asia.22 But as in other cases, Washington has been opposed to what it considers to be an objectionable claim to restrict rights and freedoms of the international community in navigation and over flight and other related high seas uses. Consequently, it has also declared the right of operational assertion in the case of the straight baselines across the Gulf of Martaban. The first of multiple assertions of rights occurred in 1985. Operational assertions against Myanmar have continued regularly; some have also been directed at requirements related to Myanmar’s EEZ. According to public records made available by the US Department of Defense, the last publicized operational assertion occurred between October 2010 and September 2011. It is clear that before President Obama in 2009 refocused US Burma policy from forcing regime change to encouraging regime transition, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) would have been quite concerned about American operational assertions. Even if overblown, anxiety among Myanmar’s military planners about possible US military intervention seems to have been a constant feature. After all, such concerns seem to have played a role in the SPDC’s decision to reject Washington’s proposal to deliver humanitarian supplies by US naval vessels in the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis.23 While the fear factor of the past will no longer be as substantial at a time when Myanmar and the United States stand to strengthen their emerging partnership, it probably should not be assumed that Naypyidaw would these days be unconcerned about deliberate US assertions directed at its maritime claims.

Hydrocarbon Deposits in Myanmar’s EEZ

As the aforementioned 2008 naval standoff between Bangladesh and Myanmar indicated, both countries are eager to exploit known and presumed offshore energy reserves. In this regard, Myanmar has for long been dependent on foreign know-how and capacity. Well before independence was achieved, foreign companies already drilled in Myanmar (e.g., Burmah Oil Company (BOC); American Standard Oil Company). Following the nationalization of the industry in the 1960s, the SPDC kick-started it anew from 1988. Since then, although production remains limited, the increasing export of gas from major offshore fields has boosted coffers. Foreign direct investment in oil and gas exploration and production, of course, proved very controversial during the SPDC years given that gas exports in particular were seen by many, especially within the international non-governmental (INGO) community, as supporting military rule while the building of related infrastructure was linked to human rights abuses. Thailand has been drawing heavily on existing production as underscored by existing Myanmar gas exports from the Yadana and Yetagun fields. With the Zawtika gas field, the largest offshore field to be operated by PTTEP (Petroleum Authority of Thailand Exploration and Production), coming on stream, a reported 25 percent of Thailand’s annual gas consumption will be sourced from neighboring Myanmar. Since mid-2013, Myanmar has also exported gas to China from the Shwe gas fields off the Rakhine coast. To date, these natural gas exports have been about one-third of those to Thailand.24

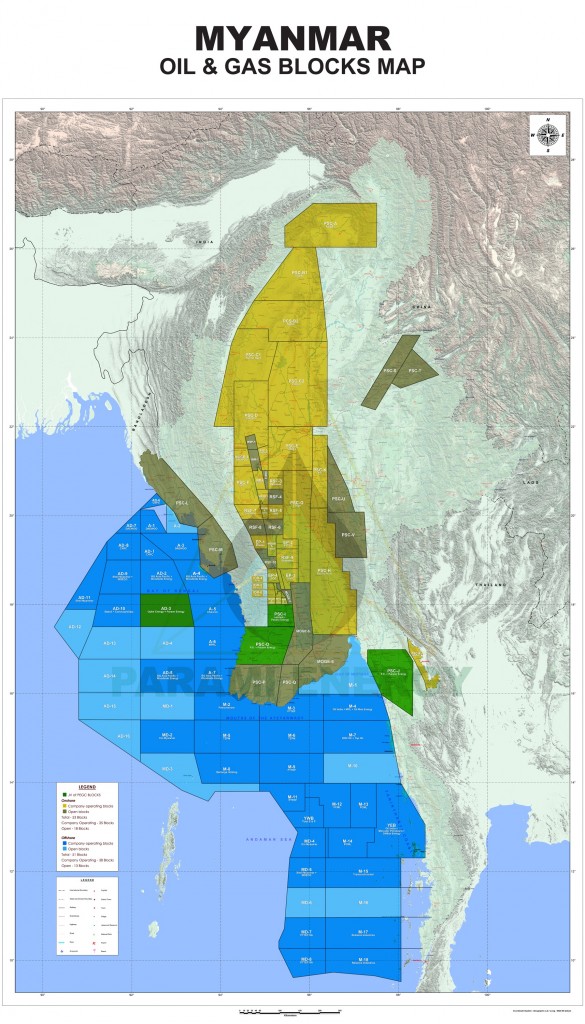

Map 4. Myanmar’s EEZ

Following the establishment of the nominally civilian government under Thein Sein, international interest in investments in Myanmar’s oil and gas industry has markedly risen. In June 2014, for instance, the Myanmar government awarded 20 international companies preliminary rights to explore. The offshore blocks comprise both deep-water ones and shallow-water ones. Myanmar has significant known deposits. However, unproven reserves are considered to be much, much higher. Myanmar’s government, given the country’s status as a net energy importer, is also keen for energy reserves to be developed and put to use for a growing domestic economy. Indeed, Myanmar’s transitional government listed the development of the energy and mining sectors as among the top seven priorities for achieving a target 8 percent annual increase in GDP. Investment in the oil and gas sector reportedly stood at USD 14.3 billion by the end of the third quarter of 2014/2015. According to a McKinsey report, the contribution of the energy and mining sector is projected to expand to USD 21.7 billion of Myanmar’s GDP by 2030.25 With the maritime boundary with Bangladesh now settled, the focus is on protecting the security of existing and future investments.

Map 5: Myanmar’s Oil and Gas Blocks

see http://www.drillingcontractor.org/still-sunny-but-clouds-are-brewing-2-32673.

Nontraditional Maritime Security Issues

Myanmar is also concerned about some non-traditional security challenges in its maritime environment. One relates to the apparent rapid depletion of fish stocks, which is linked to a combination of overfishing and illegal fishing. In this regard, the activities of Thai fishing companies, who already by the late 1980s were keen on acquiring licenses from SPDC-run Myanmar following the significant exhaustion of Thai marine resources, have been under particular scrutiny. Hundreds of foreign owned offshore fishing vessels seem to have compounded the issue of overfishing in Myanmar’s EEZ.26 But Thai companies were also allowed to fish in Myanmar territorial waters for relatively little compensation.27 Under the nominally civilian government, Myanmar has apparently discontinued some agreements over fishing rights for Thai boats. Myanmar’s fishermen have also received a boost by virtue of efforts by the current Thai military government to clean up that country’s fishery industry. Other factors have also been contributing to greater earnings, including the global decrease in fuel costs and the depreciation of the Myanmar currency, the kyat. As a consequence of these factors, the value of fisheries exports has reportedly risen from USD 40 million in 2003 to USD 144 million in 2014.28 The protection of Myanmar’s delineated maritime space is thus perhaps more important than ever.

Incidents of piracy and armed robbery have at times been a source of serious concern for some Southeast Asian governments. In recent years, such incidents have affected numerous vessels in the Bay of Bengal. Although most reported crimes refer to petty theft and robbery, mostly when ships are at anchor off Bangladeshi ports (see Table 1), some incidents have also occurred around Myanmar, often involving Singapore-flagged tugboats. Three such incidents occurred in the Bay of Bengal in 2010, one in 2011, and two in 2014. In the Andaman Sea, the last reported incident happened in 2010, involving a robbery on a Singapore flagged LPG-tanker. In marked contrast to Bangladesh, very few reported robberies have taken place with ships at anchor (see Table 2). Though numbers are relatively low, dealing effectively with piracy and armed robbery is a concern for Myanmar’s authorities.

Table1. Incidents around Bangladesh

Bangladesh (Ports/Anchorages) | Bangladesh (Seas/Straits) | Total | |

2007 | 12 | 1 | 13 |

2008 | 11 | 1 | 12 |

2009 | 18 | 1 | 19 |

2010 | 24 | 0 | 24 |

2011 | 14 | 0 | 14 |

2012 | 11 | 0 | 11 |

2013 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

2014 | 10 | 1 | 11 |

2015 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

Total | 116 | 4 | 120 |

Source: ReCAAP-consolidated incidents reports, see (recaap.org)

Bay of Bengal | Andaman Sea | Myanmar | Myanmar | Total | |

2007 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

2008 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

2009 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

2010 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

2011 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

2012 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

2013 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

2014 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

2015 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Total | 7 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 10 |

Source: ReCAAP-consolidated incidents reports, see (recaap.org)

Naval Modernization and Cooperation

The lessons learned from the 2008 naval standoff with Bangladesh and the appreciation of the diverse nature of challenges to its maritime interests seem to have been key factors in prompting Myanmar to strengthen its own naval capabilities.29 A program of indigenously built frigates, which benefit also from foreign systems, has been the result. Following the commissioning in 2010 of the Aung Zeya, the lead ship in this class, Myanmar acquired two former People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) Jianghu I class frigates, apparently as a stop-gap measure, before other indigenously built frigates would follow.30 In 2014, Myanmar’s navy, thus, commissioned the Kyan Sit Thar, and within days launched yet another frigate (Sin Phyu Shin), the third of reportedly six frigates that Naypyidaw is eager to build. There are also reported discussions with China and Russia concerning the possible acquisition of submarines.

Myanmar is promising to become more active as regards bilateral and multilateral naval cooperation. For some years, it had participated in the biannual MILAN (Meeting of the Littorals of Bay of Bengal, Andaman, and Nicobar) exchanges and exercises, but in 2013 Myanmar’s navy also embarked on a port call to the Indian mainland, involving a frigate and a corvette for bilateral exercises and patrolling in the southern Bay of Bengal. More recently, Malaysia has invited Myanmar to become an observer of the Malacca Strait Patrols (MSP) initiative to combat piracy. This initiative was formed in 2006; it comprises the Malacca Strait Sea Patrol, Eyes in the Sky, and the MSP Intelligence Exchange Group. Over the longer term, Myanmar’s navy, thus, also stands to become more integrated in collaborative efforts to address wider maritime security challenges.

Conclusion

Myanmar has had a range of maritime security issues to deal with over the years. Where it has not been directly involved as a claimant, Naypyidaw has sought to maintain a neutral and balanced stance, as illustrated with respect to the South China Sea: a neutral position on sovereignty claims, and a balanced diplomatic stance toward the claimants. Where Myanmar has been directly involved in maritime disputes, it has used bilateral diplomacy in the first instance to achieve a settlement. However, against the backdrop of a failure to agree with Bangladesh on the delimitation of their maritime boundary, Myanmar agreed to adjudication. ITLOS did not accept the full extent of Myanmar’s claim, but the advantage of having pursued dispute settlement in this manner is that Naypyidaw can take economic advantage of now having a clearly delimited EEZ. This is particularly important given that Myanmar relies on foreign technical expertise for both the exploration and production of its energy reserves. Notably, Myanmar also appreciates that the protection of its EEZ requires investment in naval assets. Over time Myanmar’s navy, thus, may yet play a more active role in addressing maritime security challenges and, perhaps, also become more involved in relevant regional cooperation.

1. Though the State Law and Order Restoration Council was able to conclude numerous ceasefires in the late 1980s and 1990s, various ethnic armed groups continued to militarily resist the Burmese armed forces (Tatmadaw) for years. The counter-insurgency efforts seemed successful as fighting declined particularly along the border with Thailand by the mid-2000s. The pressure the SPDC placed thereafter on ethnic armed organizations to transform into border guard forces met huge resistance, however, and within months of the assumption of power by the nominally civilian Thein Sein government the important ceasefire arrangement with the Kachin broke down. Shan State and Kachin State have seen considerable fighting over the last few years.

2. Andrew Selth, Burma’s Armed Forces: Power without Glory (Norwalk, CT: EastBridge, 2002).

3. Bill Hayton, The South China Sea: The Struggle for Power in Asia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 196.

4. Interview with Nyunt Maung Shein, chairman of Myanmar Institute of Strategic and International Studies, quoted in Kyaw Hsu Mon, “Burma to Seek South China Sea Resolution at ‘Pace Comfortable to All Countries,’” The Irrawaddy, April 24, 2014.

5. “ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Statement on the Current Developments in the South China Sea,” Naypyidaw, May 10, 2014.

6. Jane Perlez and Wai Moe, “China Reaches Out to Myanmar on Maritime Dispute,” The New York Times, July 1, 2014.

7. The plan was subsequently outlined to the UN secretary general and other UN members.

8. “Chairman’s Statement of the 21st ASEAN Regional Forum” (speech given at Nay Pyi Taw, 10 August 2014).

9. Yun Sun, “Myanmar’s ASEAN Chairmanship: An Early Assessment,” Stimson Center, September 2014.

10. See Maung Aung Myoe, “Myanmar’s Maritime Challenges and Priorities,” in Joshua H. Ho and Sam Bateman, eds., Maritime Challenges and Priorities in Asia (Abingdon: Routledge, 2012), 83.

11. See Andrew Selth, “Chinese Whispers: The Great Coco Island Mystery,” The Irrawaddy, January 9, 2007.

12. Maung Aung Myoe, “Myanmar’s Maritime Challenges and Priorities,” 84.

13. Ibid., 88.

14. Randeep Ramesh, “Bangladesh and Burma send warships into Bay of Bengal,” The Guardian, November 4, 2008.

15. See International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, “Judgement: Dispute concerning delimitation of the Maritime Boundary between Bangladesh and Myanmar in the Bay of Bengal,” March 14, 2012.

16. For an analysis of the separate opinion by Judge Gao and how this would serve to protect China’s position in the South China Sea, see Sam Bateman, “Solving Maritime Disputes: The Bangladesh-Myanmar Way,” RSIS Commentaries, no.48/2012 (March 20, 2012).

17. For a general discussion, see Amitai Etzioni, “Freedom of Navigation Assertions: The United States as the World’s Policeman,” Armed Forces & Society,no. 42 (January 2016): 169-191; also see US Department of Defense Freedom of Navigation Program-Fact Sheet.

18. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, November 15, 1968.

19. Maung Aung Myoe, “Myanmar’s Maritime Challenges and Priorities,” 92.

20. American Embassy Rangoon Note delivered on August 6, 1982, cited in J. Ashley Roach and Robert W. Smith, Excessive Maritime Claims, Third Edition (Leiden/Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2012), 117.

21. United States Department of State, “Limits in the Sea: United States Responses to Excessive National Maritime Claims,” March 9, 1992, 24.

22. See Department of Defense, Annual Freedom of Navigation (FON) Reports.

23. For different aspects, see Robert H. Taylor, “Responding to Nargis: Political Storm or Humanitarian Rage?” Sojourn 30, no. 3 (2015): 911-932 ; also see Jurgen Haacke, “Myanmar: the responsibility to protect, and the need for practical assistance,” Global Responsibility to Protect, no. 1 (2009): 156-184.

24. Based on data provided by the US Energy Information Administration.

25. Cited in Rakteem Katakey and James Paton, “Myanmar as Economic Miracle Hinges on Natural gas Bounty: Energy,” Bloomberg Business, June 7, 2013, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-06-06/myanmar-as-economic-miracle-hinges-on-natural-gas-bounty-energy.

26. Hans Hulst, “Fishing for Trouble,” Frontier Myanmar, October 27, 2015, http://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/fishing-trouble.

27. Myat Nyein Aye, “Fishy business: industry urges against Thai deal,” Myanmar Times, September 29, 2013, http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/business/8265-fishers-argue-against-renewing-thailand-deal.html.

28. Aye Nyein Win and Su Phyo Win, “Windfall for Tanintharyi fishermen,” Myanmar Times, November 25, 2015, http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/business/17797-windfall-for-tanintharyi-fishermen.html.

29. During the period of military rule, Naypyidaw was apparently alarmed by naval cooperation between Bangladesh and United States, not least a perceived link between a joint Bangladeshi-US naval exercise and the naval standoff between Naypyidaw and Dhaka only days later. See Maung Aung Myoe, “Myanmar’s Maritime Challenges and Priorities,” 100.

30. Koh S. L. Collin, “Political ‘New Dawn’ in Myanmar: Implications and Future Prospects for the Myanmar Navy,” Journal of Defence Studies and Resource Management 1, no. 1 (2012); also see the SIPRI Arms Transfers database.

EMAIL

EMAIL  LIST

LIST

SHARE