The primary purposes of China’s influence and interference operations in Australia are to pressure business and government to accede to China’s policy demands in the region, to weaken Australia’s historical alliance commitments, and to secure science and technology assistance in areas of strategic priority to China. These efforts are well documented.1

A parallel purpose, not to be overlooked, is message washing: laundering the Communist Party of China (CPC)’s key messages through Australia and looping them back into China for domestic legitimation purposes.

The CPC curates and channels messages through the Chinese-Australian media and the community organisations it controls for consumption by audiences in China. It does the same with prominent Australian politicians and business leaders, whom it cultivates to speak on China’s behalf on contentious policy issues or to heap ridicule on its Australian critics, in China. Eminent Australians appear frequently on Chinese television and in the Hong Kong press, criticizing their fellow nationals for failing to give China the respect it deserves. Their target audiences are not in Australia but in China.

By channelling messages from party-controlled “Australian” media networks and public figures back into China’s domestic information market, the party has created an echo chamber for telling and repeating good stories about itself from beyond its borders. Vanity carries vulnerabilities. The party’s over-riding concern for heaping praise upon itself through well-funded influence operations overseas renders it vulnerable to adverse media and community reactions, and robust legislative responses.

In China, the party’s command of the country’s media and social institutions is so complete that leaders and propaganda managers are no longer accustomed to hearing dissonance or dealing with dissent. General-Secretary Xi recently reminded his media cadres that all media platforms in China belong to the “party family” (姓党). Outside China, the role he assigns to party-affiliated media platforms is to “tell good China stories” (讲好中国故事). Drafting good China stories in Beijing and Shanghai, washing them through “Australian” media and elite Australian voices, and channelling them back into China’s domestic media as good stories about the party leadership may enhance the party’s standing at home. And yet it can generate dissonance when the messages flowing back are not in harmony with the messages going out. The practice can also discredit Beijing’s champions within Australia to the point of damaging their reputations and destroying their careers. The party and its foreign champions are vulnerable at the point where the media echo-chamber no longer echoes good China stories.

Why Australia?

While Australia has received close international attention for its exposure and response to the CPC’s influence operations, we would not want to exaggerate the significance of the Australian case. As far as Beijing is concerned this is a global story. Reuters has mapped the international expansion of Beijing-controlled Chinese community radio networks around the world.2 Cases in Europe and North America have highlighted self-censorship by major academic presses at Beijing’s request, including Cambridge University Press and Springer publishing and an authoritarian advance into Europe, over which Germany’s foreign minister has expressed concern. It is global because the CPC has decided to “go abroad” with its messaging, packaging policies and perspectives into promotional parcels for political parties around the globe, as well as for foreign media, universities, business people and community organisations. Under its “go abroad” strategy the party has extended its command over community media and social networks overseas with a view to influencing the conduct and communications of key institutions in many national jurisdictions, including Australia.

Australia has been an early trial site for China’s going abroad program. As a rule, Chinese authorities prefer to try out new ideas on a small scale, in one or two places, before adapting and extending them universally. Australia has shown itself a willing partner in many of Beijing’s experimental forays into public diplomacy, with measurably higher levels of popular good will toward China than many other liberal democracies, a complementary rather than competitive economy, and bipartisan political agreement on the importance of building good relations to secure Australia’s long-term prosperity and security.

What has changed is that, following Xi Jinping’s succession, China’s authorities have become more open in the way they present their domestic and international ambitions. The promulgation of a “New Era” for the world at the 19th Party Congress in October 2017 confirmed this approach. For China, the party has formally embraced the principle that there is nothing anywhere in China that is not under party leadership and control.3 For the world, the dawn of the New Era signals the formal end of the “hide and bide” period initiated by Deng Xiaoping four decades earlier. Xi plans to move China to the center of global power and to displace the post-war international order in the region. 4

These emerging trends have triggered a national pushback against the party’s United Front operations in Australia. Historically, operations of this kind were largely conducted under-the-radar, focusing on activities at the diaspora community level and calibrated to the “hide and bide” posture of the Reform and Opening era. By coming clean about its global ambitions in the New Era and ramping up its level of control at home and overseas, the CPC has exposed to critical scrutiny a range of influence operations on foreign territories that were barely noticed in the prior era.

Today these operations are being systematically exposed in jurisdictions where the party is not yet in a position to exercise the kind of control it takes for granted in China. Australia hosts a free press, autonomous civil society institutions, and traditions of robust public debate on matters of national importance. Along with other national governments that once overlooked China’s influence operations on their soil, the Australian government has shown by its actions that it now regards these as intrusions and considers further operations at the commercial and political levels as unacceptable infringements on national security, integrity, and sovereignty.

Why Influence China?

The idea that the CPC would bother to influence China from Australia seems counter-intuitive; yet Global Times has hinted at this all along in pointing out that Australians are deluding themselves if they think Beijing is spending time, effort, and money seeking to influence them. What in Australia could possibly be worth influencing? What could a remote, insignificant place like Australia offer a great and powerful country? What it can offer is a well-burnished mirror for reflecting China’s good stories back upon itself. Australia is a store of rare value for a party whose vanity is in constant need of stoking. It is a tribute to the success of Australian public diplomacy, not China’s, that party authorities choose Australia as a national platform for sending reassuring messages about itself to itself.

Canberra’s strategy for engaging with China has consistently painted Australia as a safe and friendly country where children can study in safety, investors can park their money with confidence, and tourists can enjoy clean air and sparkling beaches. In addition, Australian business and political leaders have shown themselves more willing than many to trade favorable perspectives on the CPC. 1 If they are overlooked by the party’s own media networks, they go out of their way to project themselves into China to show that they, too, are learning from the CPC.

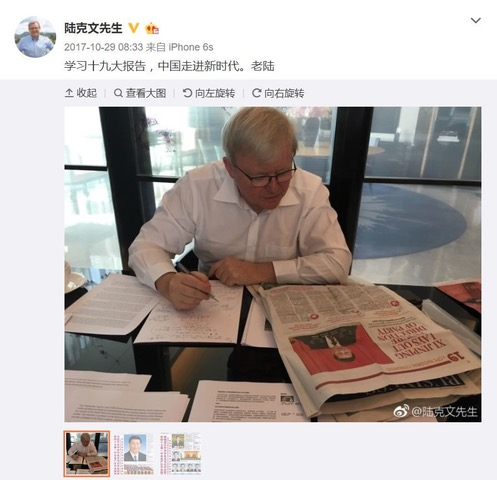

Former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s China Weibo selfie, 29 October 2017: “Studying the 19th Congress work report as China enters a New Era.”

By beaming messages from Australia into China through party-controlled media networks in China and overseas, the party leadership preens itself in front of the audience that matters most – the people of China. Party media platforms overseas and patriotic local business partners have invested millions of dollars in support of Chinese-language media platforms, schools, university centers, and political parties to project good stories about China into Australia and reflect flattering Australian perspectives on CPC ambitions and achievements for consumption by domestic audiences in China, generating an impression of international sympathy and support for Xi Jinping’s New Era that complements his domestic propaganda operations within China.

China through the Looking Glass

In March 2018, people in China and the United States were amused to find a self-styled TV journalist from America embarrassed at an official press conference in Beijing for asking a long-winded question flattering the communist party leadership. All it took to expose the journalist as a United Front plant was an eye-roll from an experienced Chinese journalist standing alongside her. The effect was devastating.5

To Australian journalists this was a familiar story. Six years earlier at a press conference for the 18th party congress in Beijing, the chair invited a credited but otherwise unknown Australian journalist to ask a question. The journalist responded with an obsequious question designed to elicit a party-friendly answer – a ‘Dorothy Dixer’ in Australian slang. When ABC journalist Steven McDonald approached the journalist afterward for an interview, he found she had been recruited a few months earlier to represent a CPC front organization in Australia, known as CAMG media.6 The journalist was planted at the conference to impress people in China, who presumably valued hearing an international perspective on China’s achievements offered by an “Australian journalist.” No-one in China was allowed to know that she worked for a Chinese-language community media network in Melbourne that was majority-owned by China Radio International and funded with the approval of the party’s Central Propaganda Department. The party was talking to itself, and to the people of China, through a party United Front organization based in Australia.

The incident highlights one of the operational innovations party agencies were testing in Australia around the time of Xi Jinping’s accession in 2012. Under the direction of the United Front Work Department and Central Propaganda Department, Chinese government media platforms were taking equity stakes in local Chinese-Australian community media companies, such as CAMG, and creating a number of front companies for the purpose of silencing independent journalists and critical voices, and evoking friendly voices in Australian-accented English to reflect back into China as authentic “Australian” stories that harmonized with stories the party was telling about itself to its people.

These innovations were not just about spreading “good stories.” The party’s media strategy in Australia involved silencing unflattering stories in independent Chinese language media and eliminating Chinese language news services on Australia’s premier state-funded media platform, ABC. ABC had long carried news and commentary deemed unacceptable by Chinese authorities, including reports on forced late-term abortions, on the unexplained wealth of top party leaders, and on Beijing’s efforts to control what was published on the internet. In an extraordinary concession to Chinese authorities, in 2015, ABC management eliminated all potentially offensivenews and current affairs programming from its Chinese-language offerings in Australia and overseas in anticipation of landing a commercial deal with state-owned Shanghai Media.7 In a series of damning revelations, ABC’s in-house Media Watch program reported that in addition to closing its Chinese news and current-affairs programs, the national media platform censored Chinese translations of its own journalists’ reports on Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s visit to China in April 2016, apparently to comply with the expectations of its Chinese partner. None of this was made public by ABC management.8

Party authorities managed to silence much of Australia’s independent Chinese community media. A decade earlier, listeners could tune in to a Chinese-language radio station in any number of Australian cities and hear the BBC World Service in Chinese or listen to open commentary on the state of affairs in China. Today, virtually all that can be heard on dedicated Chinese language radio services is local chatter supplemented by the voice of party-family media, streaming live through local radio stations around Australia via China Radio International (CRI), one of several party agencies charged with telling “good China stories” overseas. These stations are jointly owned by China’s CRI and businessman Tommy Jiang, whose Austar Media Group, or CAMG, runs a national network of radio stations, websites, and newspapers with exclusive placement contracts for Propaganda Bureau programming, successfully recreating within the Australian network the propaganda echo-chamber that envelops party media in China. CRI also works with consulates to vet guests invited to appear on its contracted Chinese-language radio programs to assess whether they are acceptable to Beijing. Australians not approved by the consulate-general are denied access to the Australian networks’ airwaves. Independent newspaper publications have also diminished relative to the Beijing propaganda broadsheets available on Australian newsstands.

By 2016, party-friendly newspapers, radio stations, and social media had come to play such a prominent role in Australian Chinese-language media that they warranted a celebratory visit to Sydney by the director of the Central Propaganda Bureau Liu Qibao. Liu made a special trip to mark the party’s achievements in a signing ceremony for six commercial propaganda agreements between party media agencies from China and private Australia media firms, in addition to the University of Technology Sydney (UTS), consolidating a number of long-standing propaganda interventions such as CAMG media and initiating several new ones. As if to validate the agreements, the acting secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Gary Quinlan, officiated on the Australian side. The signing ceremony was amply covered by media in China. China Daily reported on May 27 that the six agreements involved Xinhua News Agency, China Daily, China Radio International, the People’s Daily Website, and Qingdao Publishing Group on the Chinese side, as well as on the Australian side, Fairfax Media, Sky News Australia, CAMG, Weldon International, and Bob Carr’s Australia-China Relations Institute at UTS.

From the extensive coverage the signing ceremony received in China, it could be inferred that Liu Qibao’s visit was intended primarily for media consumption in China – to influence people in China not Australia. The event was vulnerable on the same account. Once news emerged that the Central Propaganda Bureau had chosen Sydney to celebrate its contractual achievements in silencing bad stories in community media, and placing good ones in mainstream media, the local press was onto the case.9 Liu Qibao’s conceit drew on party propaganda protocols that worked well in China but were out of place in a society accustomed to a free press. The party inadvertently embarrassed itself further when its internal reference newsletter, Cankao xiaoxi, reproduced excerpts from coverage of the event in a local journal under the title “Central Propaganda Bureau wins major victory in overseas propaganda.”10

China’s press coverage of the event undermined the credibility of local elite partners. Xinhua reported that as a result of the memorandum with Bob Carr’s UTS university centre, “myths will be dispelled and cross-cultural understanding is set to grow as China-Australia media cooperation increases following the signing of these six agreements.”11 Xinhua’s core mission is to instruct China’s media on the myths that can never be punctured and the news that can never be published. In February 2016 Xi Jinping told state media that it all belonged to “the party family.” Xinhua circulates a daily list under direction from Liu Qibao’s Propaganda Department detailing forbidden topics to be avoided by media in China – including at that time the Panama Papers – and systematically policing perennially sensitive topics to ensure that they never receive favorable mention, including freedom of the press, universal values, civil society, civil liberties, and so on. Far from dispelling myths, Carr’s center has largely perpetuated them. To satisfy its vanity, the party discredited its most capable good-story tellers in Australia.

Nonsense and the fall of Senator Sam Dastyari

None was discredited by Beijing vanity operations more than Senator Sam Dastyari (Labor NSW). Chinese-language media feeds intended to please party authorities in China loomed large in the drama that brought him down in December 2017. The clever, telegenic, and popular son of Iranian Muslim immigrants, Dastyari was promoted to general secretary of the NSW Labor Party at age 26 and elevated to a federal Senate seat in August 2014 at age 29. Following a series of embarrassing revelations, on December 12, 2017 he announced his intention to resign at the next sitting of the Senate. Dastyari was highly regarded within the Labor movement, not least because he served as a magnet for China-linked donors who contributed several million dollars to the Labor Party during his term as general secretary and senator. ABC journalist Chris Uhlman reported that China-linked sources were responsible for the largest share of foreign-sourced donations to Australian political parties, over $5.5 million from 2013 to 2015.12 The Labor Party received several million dollars over this period.

Consistent with United Front operations, the return on investment on China-linked political donations was largely unrelated to the donors’ legitimate business interests in Australia and more closely connected with China’s strategic interests in the region, as seen in reports that a political donation promised to Labor was being withheld as punishment for not delivering sufficient returns to Beijing. In September 2016, Fairfax journalist Chris Hartcher reported that Chinese donors withheld a large payment that would otherwise have been given to Labor if the party had softened its position on China’s claims to the South China Sea. He concluded “this is an attempt at deep, strategic corruption, an effort to pay politicians to change Australian foreign policy.”13

In the case of Dastyari, donors secured a flow of media commentary into China in support of China’s foreign policy positions on sensitive issues, including Beijing’s claim on contested territories in the East China Sea and South China Sea. His support for China’s party media extended to a personal video message delivered via People’s Daily Online congratulating the communist party mouthpiece for the “incredible work that it does to actually build the relationship between Australia and China and make sure that there is a strong voice for Chinese Australians.”14 This message was delivered to China after communist party operatives had bought out most of the viable autonomous radio and newspaper platforms once owned and run by Chinese Australians and had largely silenced critical Chinese-Australian voices on its media platforms.

In return, Xinhua and other party-linked media ensured that Dastyari found a voice for himself among Chinese Australian electors and in China. This is where the senator came unstuck. While making presentations at China media conferences, not intended for other ears, he attacked Australian government positions on regional security, contradicted his own party’s position on the South China Sea, and mouthed expressions widely used in CPC propaganda but otherwise little known in Australia, even among Chinese-Australian communities. He appeared to be speaking to someone else’s script.

As early as July 2014, according to Rowan Callick, Dastyari offered quotes to Chinese media criticizing Prime Minister Abbott for the welcome he extended to Japanese prime minister Abe Shinzo.15 In an interview with Chinese media in 2015, Dastyari was quoted mouthing communist party talking points, disputed by historians16, on the sensitive issue of Japan’s brutal occupation of China from 1937 to 1945.17 Primrose Riordan reported that at another Chinese-language media press conference in June 2016 Dastyari “pledged to respect China’s position on the South China Sea… He has also urged Australia to drop its opposition to China’s air defence zone in the contested region.”18 These alleged statements contradicted Labor Party policy and the bipartisan approach adopted by Australia’s major political parties.

Dastyari’s comments escaped the attention of mainstream English language media until Riordan’s report appeared two months later. At that point Dastyari objected that he had been caught off guard at the Chinese-media press conference in June 2016 and had muttered an incoherent response to a journalist’s question, which he implied should not be taken seriously. He insisted that he always supported his party’s position requiring Beijing to recognize the decision of the Arbitral Tribunal. Riordan’s revelation followed immediately on another story about a China-linked company paying an office travel bill at Dastyari’s request. Party leader Bill Shorten demoted him from his positions as shadow minister and head of opposition business in the Senate. He retained his Senate seat.

Early in 2017 Dastyari was restored to favor in Labor circles and appointed deputy opposition whip in the Senate. In October, however, he was damaged by further revelations, in one case claiming he had recently warned a Chinese national Labor Party donor that his phone may be tapped by Australian intelligence services, in another, that a transcript of his previously-reported 2016 press conference had surfaced showing that far from uttering an incoherent response on the South China Sea dispute, he read from a prepared script.19 In November he was demoted once again, this time from deputy opposition whip.

The stories kept coming. Early in December 2017 the Sydney Daily Telegraph found after reviewing Dastyari’s record of questioning at Senate Estimates Committee hearings that he had grilled senior Defence Department and Foreign Affairs officials with over 100 questions on China and Japan policy from perspectives reflecting China’s concerns, generally considered inappropriate in Senate Estimates hearings.20 On December 10 a Fairfax investigative team reported that in 2015 Dastyari had urged Labor’s foreign affairs spokesperson Tanya Plibersek to abandon a planned meeting with a renowned Chinese-Australian democracy activist in Hong Kong for fear of offending “figures in the Chinese community in Australia,” presumably political donors.21 Dastyari denied all wrongdoing. But two days later, he announced that he would surrender his senate seat in the new year.

The Chinese Communist Party Is Not What It Is

In the wake of his demotion in the party and his resignation from the senate, one of Dastyari’s powerful allies called for an end to United Front activities in Australia, as if these were incidental to their China engagements. In December 2017, former foreign minister Bob Carr called for closing down the Australian Council for the Promotion of Peaceful Reunification of China (ACPPRC). “Whether its links with China’s United Front Work Department are vestigial or active, they are now a distraction,” he explained.22 The ACRI centre at UTS, Carr’s own China institute, was founded with a grant from the sitting ACPPRC president, who boasted of selecting Carr to run it, and personally chaired its advisory board. The communist party’s propaganda chief signed an agreement with Carr’s centre. Were it not for his backers and partners in communist party and its United Front arms such as the ACPPRC, Carr would have had little incentive to tell good China stories and possibly no platforms from which to tell them.

Carr’s advice to close down the ACPPRC was not only self-serving but ill-informed. The CPC is not what it purports to be, a political party, and its United Front strategy is not something that can simply be jettisoned at will. 23 The United Front is integral to party operations and United Front agencies such as the ACPPRC are essential if the party is to do what it does best – secure advantage by winning powerful allies and silencing and discrediting critics. Its United Front strategy is one of very few means the party has for dealing with people and entities outside itself, including most of China and all of the world at large. It has few ways to relate to a country such as Australia without drawing on United Front puppet organizations, media, and friendly spokespersons.

The CPC won’t change because it is not a political party in the normal sense of that term. It more closely resembles a sovereign state than a political party. Like a national state, the party owns and controls China’s entire military apparatus. The PLA, army, navy and air force, are not arms of government but armed wings of the party. Elsewhere this is considered a core characteristic of a sovereign state. Second, the party is above the law of the state. The party constitution takes priority over the state constitution, which is in effect a supplementary clause of the party constitution. This party prerogative is a mark of sovereign state constitutions in other national jurisdictions. Third, Party members are outside the law, in the sense that they are not generally subject to China’s justice system while they remain party members. Party members use the national policing and justice system as a tool for disciplining China’s 1.3 billion people, who inhabit the world ‘outside the system’ (体制外), as party members quaintly refer to the world beyond themselves. Further, only those “inside” (体制内) as system insiders call themselves, are entitled to participate in politics – to speak, act, and organize politically by virtue of who they are. This is the sign of a political nation elsewhere. Finally, party members manage and staff the institutions that ‘lead everything’ in China. By Xi’s decree, there is not a single institution in China that is not led by the communist party. Taken together, these are the characteristics of a sovereign state. To ask the party to change its spots is in effect to challenge its sovereignty.

What does this mean for the party’s relations with those outside itself, in China and abroad? This is where the United Front comes in, as a mechanism for inviting “outsiders” to enjoy some of the privileges otherwise reserved for “insider” party members, including the right to participate in politics. Party members aside, no one in China can utter a word in public about politics without a United Front invitation. Once invited, however, non-party members are expected to “actively participate in politics” (积极参政), as the party puts it. To be inactive would be to abuse the privilege of an invitation. Once an invitation is accepted, an “outsider” can enjoy the benefits of civic engagement and “actively participate” with the party in achieving its objectives. It follows that any request to close down United Front operations in Australia is likely to be ignored in Beijing. Without its United Front operations, the party can neither be what it is nor do what it does. Its success in co-opting Australian elites confirms the value of its United Front strategy. Why should it change?

The ease with which retired politicians and active business people, university presidents, and upper leadership stratum have been co-opted into the party’s United Front strategy reassures Beijing that liberal democracies are easy targets for influence operations. Party leaders know from experience that “capitalists,” as they call them, will sell anything to secure a private advantage. This insight underlay the party’s resounding victory in the mid- 20th century and it underpins the success of its United Front strategy in Australia in the 21st century. In so far as the party’s influence operations are designed to flatter the Chinese leadership, as well as influence Australia, its champions in Australia can rest assured that the party is unlikely to shut them down any time soon.

Conclusion

The party’s influence operations in Australia have come to mimic, on a modest scale, the propaganda echo chamber that party propaganda experts have constructed for themselves in China. They accomplish this overseas by buying equity and space in foreign media operations and by commissioning influential foreigners to repeat their talking points abroad for rebroadcasting into China, to flatter the vanity of senior party leaders. Along the way, party functionaries have come to assume in foreign jurisdictions many of the powers and privileges they take for granted under authoritarian rule at home. In the case of Australia, they silence bad stories, doctor texts, and entice institutions such as the ABC to do the same. They buy up community media to silence critical voices, and they undermine the commercial viability of independent Chinese community media by threatening to close market opportunities in China for firms that advertise in independent media outlets. They monitor publications and appearances in Chinese-language media by community members with a view to preventing their publication or appearance if they step out of line. They guide existing Chinese community associations in Australia to speak out in favor of China’s foreign and domestic policies, and to ostracize sceptics and critics within communities with a view to silencing them. They create ab initio local chapters of global United Front “NGO” organizations, under embassy and consular guidance, to pursue China’s foreign policy objectives by co-opting leading Australians from all walks of life to endorse Beijing’s vision and policy objectives.

And yet the strategy has its flaws. The strengths and weakness of the party’s approach to elite co-option and media manipulation are well illustrated in the rise and fall of Senator Dastyari, who owed his initial rise in the Labor Party to his capacity as a political fund-raiser, raising funds from business people with China connections. China-linked donations accelerated his elevation in the Labor Party and later into federal office. After just four years in the Senate, however, he was compelled to step down in the face of a torrent of press reports, some arising from comments he made to China’s party media that were inconsistent with his own party’s policies and Australian government policy on China. His difficulties with mainstream Australian media often revolved around what he said in front of Chinese media for consumption in China. These had little to do with efforts to influence Australia.

None of his indiscretions amounted to a sackable offense in Australia’s robust party-dominated political culture. Opposition leader Bill Shorten twice stripped Dastyari of responsible positions in the Labor Party and regarded these demotions to the back bench as sufficient “punishment” for Dastyari’s “poor judgment.”24 The trigger for Dastyari’s resignation was cumulative pressure building up through a continuing flow of news about his “poor judgment” leading into the final week of a federal by-election. Reports would not stop coming during a by-election that Labor needed to win if it was going to undermine the conservative coalition’s majority in the federal parliament outside of a full-scale federal election. In this electoral setting, the senator’s adverse media profile presented a serious political distraction.25

Dastyari’s demotion and resignation were preceded by press revelations over several years. Australia’s free press has been described as a “magic weapon” for combatting China’s influence peddling abroad, uncovering Dastyari’s indiscretions and exposing the Chinese government’s abuse of Australia’s open and inclusive democratic system.26 And yet the comments he made to media which did him gravest harm were to communist party “family” media, not to independent Chinese language media or mainstream English language media. A striking feature of Dastyari’s demise was the role of the unfree press – China’s party-sponsored media in Australia – in exposing him to criticism by the free press.

Donors linked to the party’s United Front operations were not well served in the case of Dastyari. They earned a return on investment while he was in office, in the form of frequent media appearances, but they did little to shift policy in favor of China’s geopolitical claims in the region. As one donor, a Chinese national, summarized his key take-away, “we need to learn … how to have a more efficient combination between political requests and political donations.” 27

Party headquarters was not especially well served either. The sole purpose of Chinese media at home and abroad is to defend and sing the praises of the party – in the words of Xi Jinping to “protect the authority of the party centre, protect party unity, love the party, protect the party, serve the party.” This is not a message that translates well in an open and inclusive liberal democracy. China’s party-family media are proving to be a liability in Australia.

The party media openly courted Dastyari from the outset, initially over his term as general secretary, and later as a federal senator for the Labor Party. Mainstream journalists with a command of Chinese needed only to probe authorized Beijing media outlets to discover a trove of his commentary and footage commending Xi Jinping and the CPC and Chinese government, duly translated into Chinese and transmitted to China and the wider Sinophone world, that had not been previously reported in mainstream English language media. Efforts by China’s party media to project favorably on the CPC, from within Australia, did him serious damage. In the Dastyari case, the combination of an unfree press, a free press, and electoral democracy served Australia well. If the Australian experience offers any guide, the vanity of a party leadership that insists all affiliated media at home and abroad must love, serve, and protect the party could prove to be a serious vulnerability in CPC operations in other nations.

1. a href=”#_ednref1″ name=”_edn1″ title=””> Clive Hamilton, Silent Invasion (Melbourne: Hardie Grant, 2018).

2. Koh Gui Qing and John Shiffman, “Beijing’s covert radio network airs China-friendly news across Washington, and the world,” Reuters, November 2, 2015.

3. In January 2016, Xi Jinping declared that “the party leads everything” (党领导一切), a phrase subsequently inserted into the party constitution at the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, http://www.360doc.com/content/16/0111/21/79186_527195369.shtml

4. See Michael D. Swaine, “Chinese Views of Foreign Policy in the 19th Party Congress.” China Leadership Monitor, No. 55, January 2018, http://carnegieendowment.org/files/clm55-ms-final.pdf

5. Paul Mozur, “A Reporter Rolled Her Eyes, and China’s Internet Broke,” The New York Times, March 13, 2018.

6. Stephen McDonell, “China uses mysterious Australian to rig Congress coverage,” ABC, November 14, 2012.

7. John Fitzgerald, “Was the ABC shanghaied by Beijing?” Inside Story, April 18, 2016, http://insidestory.org.au/was-the-abc-shanghaied-by-beijing

8. Mediawatch, Episode 15, May 9, 2016, http://www.abc.net.au/mediawatch/transcripts/s4458872.htm

9. John Fitzgerald and Wanning Sun, “Australian media deals are a victory for Chinese propaganda,” The Interpreter, May 31, 2016, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/australian-media-deals-are-victory-chinese-propaganda; Philip Wen, “China’s propaganda arms push soft power in Australian media deals,” Sydney Morning Herald, May 31, 2016, http://www.smh.com.au/business/media-and-marketing/chinas-propaganda-arms-push-soft-power-in-australian-media-deals-20160531-gp7yz6.html

10. “Central Propaganda Bureau wins major victory in overseas propaganda,” Cankao xiaoxi, June 2, 2016.

11. “China-Australia media cooperation to increase cultural understanding,” New China, May 27, 2016.

12. Chris Uhlmann, “Australian businesses with close ties to China donated $5.5m to political parties, investigation shows,” ABC News, August 22, 2016, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-08-21/australian-groups-strong-ties-china-political-donations/7768012

13. Peter Hartcher, “Sam Dastyari: Riding the red dragon express not a good look,” Sydney Morning Herald, September 3, 2016.

14. http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/all-the-hallmarks-of-an-infomercial-abc-under-fire-over-sam-dastyari-australian-story-episode-20170731-gxmmgq.html

15. Rowan Callick, “China paper hailed Dastyari’s hit on Tony Abbott Japan speech,” The Australian, September 8, 2016, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/foreign-affairs/china-Paper-Hailed-dastyaris-Hit-on-Tony-Abbott-Japan-speech/news-story/2424d630a63b74588a1c2611e85cf7e3

16. John Fitzgerald, “China’s Anti-Fascist War Narrative: Seventy Years On and the War with Japan is Not Over Yet," The Asan Forum, November 17, 2015.

17. James Massola and Nick McKenzie, “Sam Dastyari under renewed pressure in Parliament as new Chinese interview surfaces,” Sydney Morning Herald, December 4, 2017, http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/sam-dastyari-under-renewed-pressure-in-parliament-as-new-chinese-interview-surfaces-20171204-gzyaag.html

18. Primrose Riordan, “Sam Dastyari pledges to support China on South China Sea beside Labor donor,” Australian Financial Review, August 31, 2016, http://www.afr.com/news/sam-dastyari-pledges-to-support-china-on-south-china-sea-beside-labor-donor-20160831-gr5mwk#ixzz4JGmyVqe8

19. Nick McKenzie, James Massola, Richard Baker, “Sam Dastyari defends Chinese government in secret tape,” Australian Financial Review, November 30, 2017, http://www.afr.com/news/politics/national/all-at-sea-shanghai-sam-dastyari-the-whale-and-the-lost-tape-recording-20171129-gzvde2#ixzz57W5BxPUa

20. Sharri Markson, “Senator Sam Dastyari hounded top defence officials with questions on China’s concerns over 115 times,” Daily Telegraph, December 7, 2017, https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/senator-sam-dastyari-hounded-top-defence-officials-with-questions-on-chinas-concerns-over-115-times/news-story/eaf02cad85ee4534a45883e06a064a1e?login=1

21. Fergus Hunter and Nick McKenzie, “Sam Dastyari warned Tanya Plibersek to abandon meeting with Hong Kong activist, sources say,” Sydney Morning Herald, December 10, 2017, http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/sam-dastyari-warned-tanya-plibersek-to-abandon-meeting-with-hong-kong-activist-sources-say-20171210-h01z5o.html

22. Bob Carr, “Seven steps to tame fears over China,” The Australian, December 12, 2017, http://www.australiachinarelations.org/content/seven-steps-tame-fears-over-china

23. The party courts international recognition as a political party. In November 2017 it convened the inaugural “World Political Parties Dialogue” in Beijing, attended by 300 political parties from 120 countries, including the US Republican Party, the French Republican Party, and the UK Conservative Party. Those that accepted the invitation encouraged the CPC in the belief that it is, like them, simply a political party, http://www.xinhuanet.com/world/2017-12/03/c_1122050731.htm

24. ABC News, November 30, 2017, https://www.msn.com/en-au/video/news/shorten-says-dastyari-showed-poor-judgement/vi-BBFWFDj

25. Michelle Grattan, “Dastyari quits the Senate after pressure over his China links, The Conversation,” December 12, 2017,

http://theconversation.com/dastyari-quits-the-senate-after-pressure-over-his-china-links-89027

26. Kelsey Munro, “A free press is a magic weapon against China’s influence peddling,” The Interpreter, December 18, 2017.

27. Huang Xiangmo 黄向墨, “在澳华人政治捐款可理直气,”环球时报,” August 29, 2016, http://opinion.huanqiu.com/1152/2016-08/9369062.html. First reported in Angus Grigg, “Chinese businessman complains MPs ‘not delivering’ for donations,” Australian Financial Review, August 29, 2016, http://www.afr.com/news/world/asia/chinese-businessman-complains-mps-not-delivering-for-donations-20160829-gr3xv8#ixzz57RNdVnij

EMAIL

EMAIL  LIST

LIST

SHARE